An innovative technique developed by Dr. Alisa Vig

Background

A variety of visual tools are implemented to treat children with ASD or other special needs to encourage progress in therapeutic goals. Visual support can also be effective for promoting continuity, intentional communication, and message planning and organization.

Visual aid can assist with:

- Planning- A parent can help their child plan the schedule with drawings or pictures representing events in the daily routine, including playtime, bath time, and dinner.

- Organize gratification delay – The child sees before her options (playground time, a board game, and a visual representation of farewell) and organizes them together with her therapist to decide how the session will play out.

- Communicate intent- a verbally-challenged child plays with a doll and is exposed to pictures representing activities related to the doll. With the visual aid, he can communicate the activities he intends to engage in with the doll in a nonverbal manner.

- Social Stories – Using social stories, a parent can prepare their child for the birth of a sibling, moving houses, or starting a new school.

What is unique about dynamic drawings?

Dynamic drawings activate visual engagement; however, unlike other treatment tools, they focus primarily on emotional processing and building symbolic and abstract thinking ability. The name “dynamic drawing” originates from the drawing changing throughout the treatment following the child’s dynamic emotional profile

The method stands out for its interdisciplinary nature.

It is founded on neurobiological research indicating sequencing, integrating, and auditory and sensory-motor input processing difficulties in children with ASD and other special needs. This tool is based on children’s unique needs and takes into account their processing and attentional abilities. Dynamic drawing is aided by visual support, associations, and communication circles tailored to the child

Emphasis is placed in this treatment method on accompanying the auditory (auditory) and visual (visual) channels in an accommodating manner that allows the child to process the emotional experiences and messages effectively.

In implementing this method, the therapist or parent creates moments of shared attention, focus, dialogue, and communication circles relating to a situation that has induced happiness, fear, anger, or other strong emotions in the child. The activity is conducted as a conversation with the adult accompanied by a dynamic drawing. The interaction’s complexity depends on the child’s abilities but is usually guided by a short text and slow-paced dialogue. The method is incredibly impactful during the interaction and has positive long-term effects, helping the child process similar strong emotions brought about by future events. Symbolizing the emotionally-charged event without re-engaging in the experience allows the child to progress in their regulation and emotional processing and develop symbolic and abstract thinking abilities.

When should dynamic drawings be used?

- In situations of emotional complexity (anger, frustration, sadness, separation difficulties, etc.)

- When a child has difficulty with independent problem solving

- In treating children with sensory-emotional regulation difficulties.

After an initial introduction dynamic drawings may be used in FLOORTIME as well as throughout the day.

What are the goals of dynamic drawing?

- Emotionally processing challenging situations for the child

- Improving the child’s symbolizing ability

- Emotional regulation – advancing emotional regulation abilities in a way suited to the child’s sensory profile

What is needed for dynamic drawings?

- An adult to ask emotionally-centered questions

- Paper and writing instruments

Guidelines for dynamic drawing

- Invite the child to the drawing

- Draw characteristics of the event while engaging in dialogue with an emphasis on communication circles and co-regulation

- Signify emotions with symbols such as facial expressions (sad face, smiley face), hearts to indicate love, and so on

- Imbed verbal messages with the use of speech or thought bubbles

- Illustrate dynamic emotions through the drawing by changing elements, such as redrawing sad faces into happy ones to encourage optimistic thinking or rewriting a sad thought-bubble into a motivational one

- End with something positive (important!)

- Review the drawing with another significant adult in the child’s life to better understand its impacts on the child’s emotional profile.

What should I pay special attention to when I do dynamic drawing?

- Conduct the interaction at a slow pace

- Maintain a helpful and positive tone

- Create communication circles.

- A changing drawing that effectively depicts the variety of emotions which form and shift in the child during the situation.

- Encourage the child’s shared attention throughout the process. Ensure that the child sees both the painting and the adult who presents him or herself in the situation.

Examples of the use of dynamic drawing with children of different ages and capabilities:

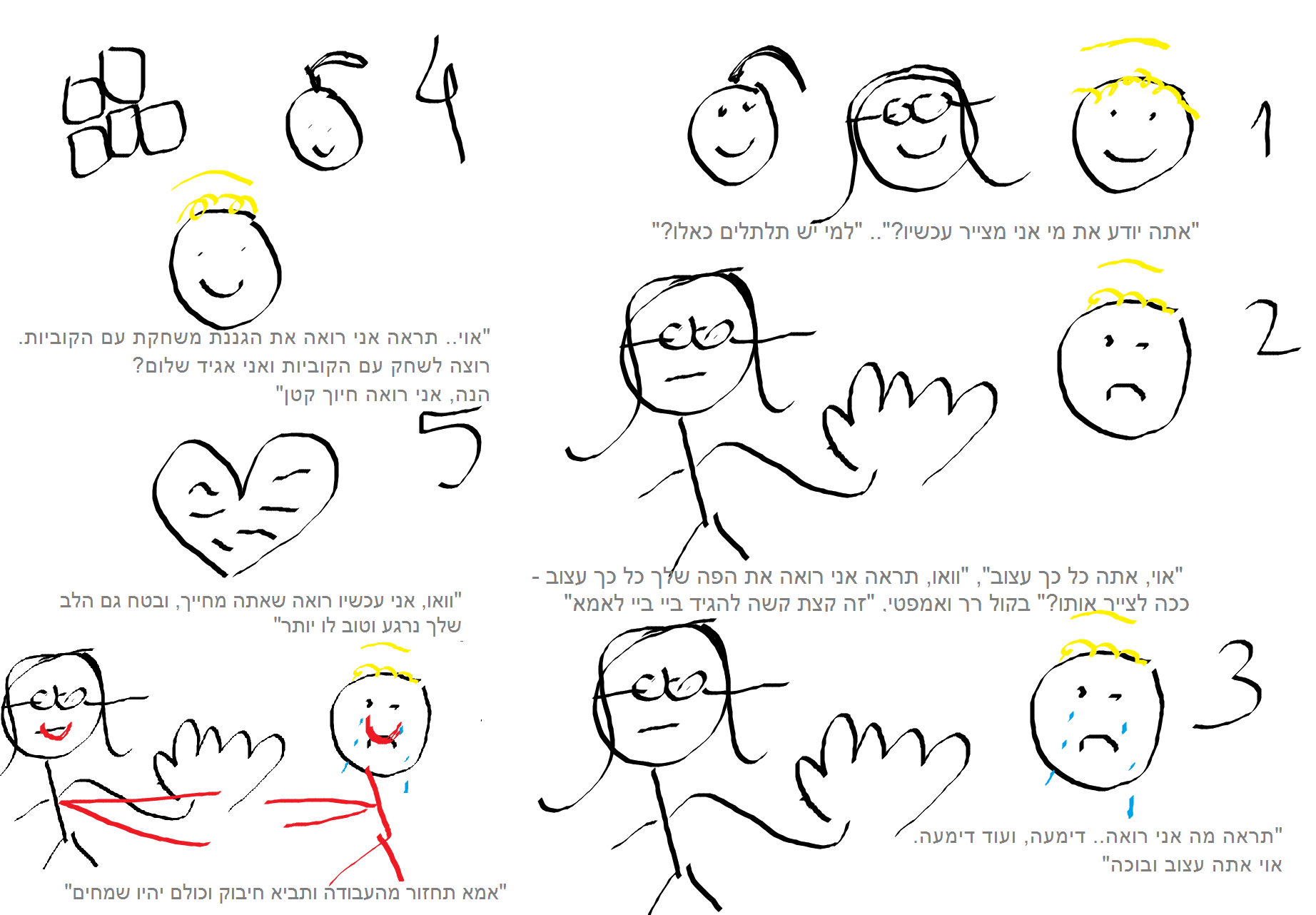

תיאור מקרה 1: ילד בן 3 , גן תקשורת

A child arrives at the kindergarten with his mother and is afraid to enter. He cries and protests, clinging to his mother’s pants. To help the child process the situation, the mother asks for a piece of paper and draws the external characteristic of the child – a kippah, light hair with curls, etc. She asks in an empathetic voice, “Can you guess who I’m drawing?” Thus inviting the child to interact.

She continues to draw herself and the teacher.

The drawing changes as the story it is depicting progresses; at first, the child is sad and finds it hard to say goodbye to the mother. The mother softly speaks as she draws, saying, “Oh, you are so sad, wow, look, I see your frowning face, how should I draw it?” She empathizes with her child, continuing, “It’s a little hard to say goodbye to Mom. Look, what is this I see? A tear” (and draws tears). She shifts to recollecting and drawing emotionally-positive factors in the situation. Drawing the teacher that the child loves and the game corner, she encourages him, “Soon you will go play games with the teacher and be happy.” After the child calms down and smiles a little, the mother can now say, “Wow, I see that you’re smiling. Give me a hug, and we can all be happy.”

Emphasis: The dialogue is conducted using multiple communication circles and at a slow pace to allow emotional processing and the development of symbolic comprehension. Because of the child’s young age, vocalizations and a slower speech rate are emphasized.

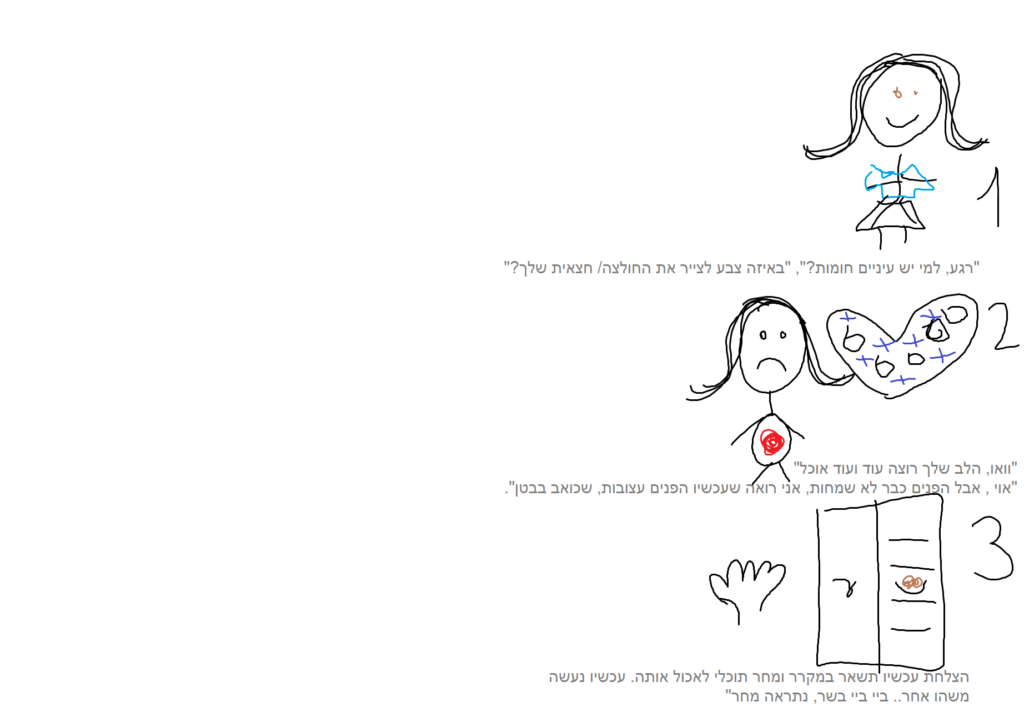

Example 2: 10-year-old Yael attends a special education school. The situation depicted happened at home.

The difficulty arose in a joint encounter between the father and his daughter relating to compulsive behavior surrounding food, her need to finish what is on the table regardless of satiety. The girl stood to take the remaining meat stew even though she was full.

The father encouraged Yael to sit at the table for another moment. He begins a dynamic drawing in which he depicts Yael in detail. He engages communication circles to promote co-regulation, asking questions like, “Wait, who has blue eyes? What color should I paint the shirt?”

He progresses to depictions of the impulse and the harmful impact Yael would experience if she listens to it, “Wow, your heart wants more and more food, but, oh, your face is no longer happy. Look, I can see how your stomach hurts”. Yael’s father draws the plate with leftovers in the fridge she can eat tomorrow. He says, “You can eat this tomorrow, now let’s go do something else. Goodbye, meat stew, see you tomorrow!” Yael detaches from the meat and plays instead with her favorite stickers. Her father has successfully guided her past the compulsive behavior by use of dynamic drawing.

Emphasis: In this case, Yael has poor auditory processing. There is a marked need for co-regulation, slow pace, and multiple communication circles.

Example 3– A 12-year-old ultra-Orthodox girl in communication-development class

The girl’s psychological treatment was accompanied by work on a whiteboard and some paper work to help her process complex emotional experiences.

The girl came during the High Holy Days for a session and was silent. After a few minutes, the therapist drew a picture of a girl and above the drawing a question mark and told her, “I see you have many thoughts, but I don’t know what you are thinking.”

The girl responds by explaining that she is especially afraid of Yom Kippur because “I don’t know what God will decide and what will happen to you, I’m very afraid.”

The dialogue continued to the subject of holidays in general, discussing which holiday brings her the most joy (Sukkot, because of the decorations) and which holiday scares her (Purim, because of the noisemakers and the drunken adults).

The therapist wrote to her, “You have a lot of thoughts, and when you didn’t tell me, I couldn’t know if you were sad, happy, scared, or excited.

Sounds to me like you’re a little excited and a little scared. You have a lot of feelings!”

Using dynamic drawing on paper allowed a conversation to proceed about the patient’s fears of things under her control and those that aren’t. The initial conversation led to a discussion regarding the girl’s sensory profile, especially her high sensitivity to noises. It also served to regulate her emotions, inducing positive emotions in the girl when she spoke about her favorite holiday. Following the session, a similar conversation was conducted by her parents regarding her sensory difficulties and the difficulty of distinguishing between reality and imagination during Purim (masks). The dynamic drawing introduced at the beginning of the treatment made it possible to progress to a more in-depth dialogue. The experience served as an anchor for talks in the following weeks.

An emphasis was placed in this case on promoting higher verbal processing and the ability to utilize drawing and text to reach more complex emotional discourse. Visual support is given both through drawing and text.