What is the goal of the neuro-geometric approach?

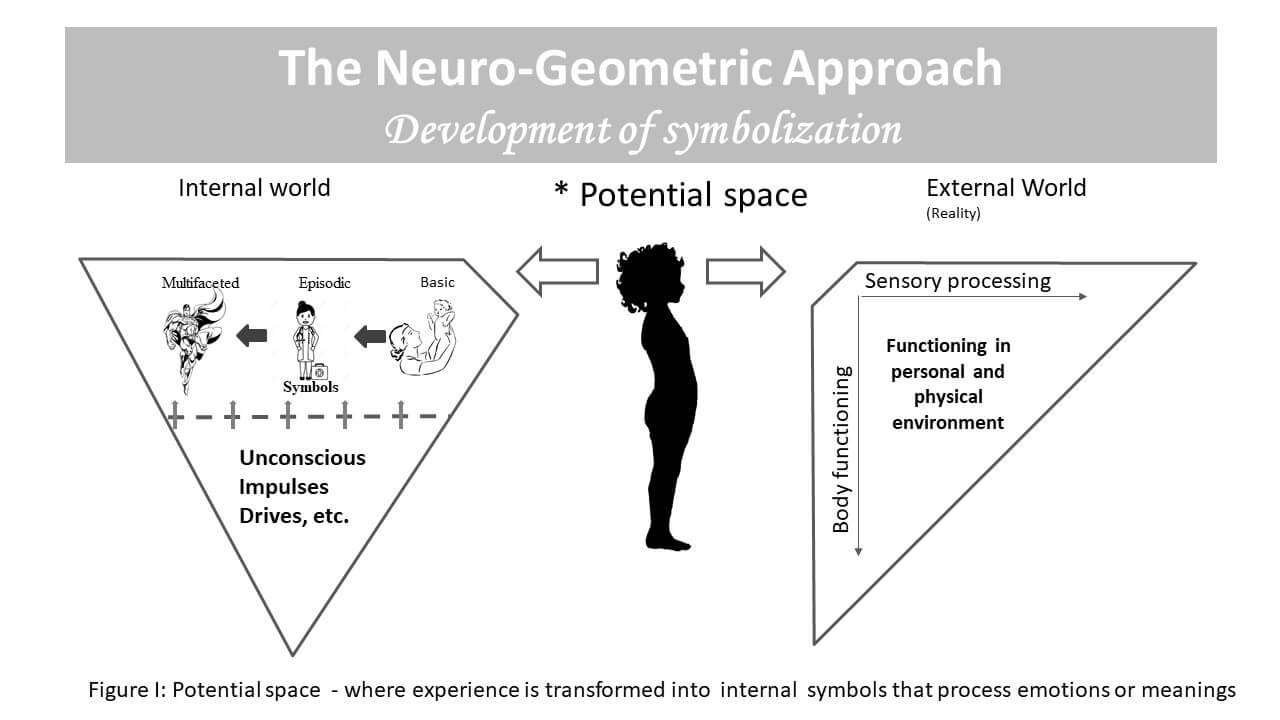

The neuro-geometric approach allows children to build an internal 3-D map that parallels the interactions and experiences of their external worlds This map allows for emotional processing and regulation and encourages symbolic thinking and play.

THE BASIS OF THE APPROACH

The neuro-geometric approach is based on the DIR model, diverse psychological theories (psychoanalytic, relational, and developmental), and studies in the neuropsychological and neurobiological field. It analyzes the child’s sensori-motor profile and their various sensitivities, such as a child’s difficulty to process numerous stimuli proportionately that may lead them to excessive visual focusing. The method likewise recognizes the child’s emotional and psychological needs, which include receiving feelings of security and pleasure from his or her environment and avoiding pain (Freud). More complex needs and experiences emerge in later stages of development, including processing pain, jealousy, or fear.

Who is the approach suitable for?

The approach is suitable for treating children, especially those with special needs, including children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) children with anxiety, children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, and more.

Launch of the Neuro-Geometric Approach by the Israeli Association for Child Development and Rehabilitation:

MAIN OBJECTIVES

- 1. Support the child’s emotional regulation

- 2. Expand the child’s symbolizing ability while internally and externally mapping daily emotional experiences

BASIC TERMINOLOGY

-

Points :

- describe the first experiences of an infant in the world, chaotic and fragmented. An infant may hear voices and see people talking, but not necessarily connect between them. Points depict partial, data-based experiences led by an infant’s impulsive attention span, recording the number of toys in a room, the texture of a blanket, or the smell of food. The infant’s points of attraction have no depth or volume, and she goes solely after her senses. Points have fleeting importance and no mental record in the inner world of the infant.

-

Lines:

- describe experiences and interactions in the relationship between a child and their caregiver.

Lines are “drawn” in bonding moments embedded with sight, voice, or touch. The lines reinforce a mental representation of the world the child experiences and form caregiver memory. The baby may expect and search for her mother, even when she disappears from the visual field, as the baby now has her image in her mind. This image is drawn from lines previously created in interactions between mother and baby throughout their relationship. A child who has dysfunction in one of his sensory systems will have difficulty locating his mother in space. - For example, he may lose visual focus when she moves about the room. In this case, the visual-spatial line can break or fade, and his mental representation of her will diminish. The caregiver may, in this case, stimulate other senses to re-engage the child, form a new line and strengthen the connection. For the visually-spatially challenged child, his mother may intermittently touch his hand or sing a song as she moves about the room, in this way reassuring him of her presence and reinforcing the line between them. Later, the mother may read a bed-time story and give him a goodnight hug, forming new lines that continue to strengthen and build his mental image of his mother. Lines’ characteristics are varied and include length, space, clarity, endurance, directionality, axes (up-down, side to side, and diagonal), sensory modalities (visual, auditory, tactile, etc.), continuity (flow vs. broken), and mobility of the child, parents, or both parties.

- describe experiences and interactions in the relationship between a child and their caregiver.

-

Triangles and Polygons:

- Shapes are formed in time as children develop stronger connections with their parents and continue interacting with their environment. The caregiver’s images are saved in their consciousness. From this secure point, they are free to explore other people or objects that capture their interest. A triangle emerges when the child shares her new experiences with the parent-image in her mind, drawing lines between the child, significant figures in her life, and the new experience. Triangles represent joint attention. Polygons are created from four or more additional points, including the child and three or more additional objects or individuals, such as a Four-Square game between the child, three additional children, and a ball. All lines, whether between two points, three (triangles), or four and more (polygons), share defining attributes, such as size, length, width, flexibility, and mobility.

-

Polygons:

- Polygons are created from four or more additional points, including the child and three or more additional objects or individuals, such as a Four-Square game between the child, three additional children, and a ball. All lines, whether between two points, three (triangles), or four and more (polygons), share defining attributes, such as size, length, width, flexibility, and mobility.

-

Time:

- Time is a fourth factor, separate of points, lines, triangles and polygons, representing the duration of perceptual, visual-spatial, and emotional experiences described by the other factors. In the early stages dominated by points, before mental images are formed, a child is yet to perceive time. They may continue an activity for an extended duration without any meaningful change since time has little effect on the event (e.g., turning a wheel). Later, as she develops expectations that her parents will interact with her, she begins to give meaning to time during the formation of lines. She will incorporate her observations of the parents’ day-to-day activities across time and space into her play. For example, seeing dad cook dinner, she later pretends to make dinner for her doll. The perception of time develops and affects the child’s emotional world and her ability to create meaning and symbols. She can now anticipate upcoming situations and understand her parent saying, “Mommy will come soon!” or “Tomorrow we will go to the dentist.” The child’s evolving sense of time allows her to express past, forthcoming, or imaginary events in her play.

Stepping stones in symbolic development

STAGES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF SYMBOLISM

Basic Symbols:

Children’s ability to create an emotional representation of the primary caregivers in their life. The child imagines the parent even when he does not see him. For example, the child hears the parent’s voice from the kitchen and realizes that a bottle will arrive in a moment.

Possible Therapeutic Tools:

- Affective container : is a therapeutic method in which the parent or therapist guides the emotional tone in the environment to reduce anxiety and increases bonding and synchronization in parent-child interaction by the use of affective tools like playfullmess, dramatization and vocalization.

- Affective Focus : The caregiver adjusts his or her voice, gaze, proximity, and movements in relation to the child in order to regulate and focus the child and promote line development. The caregiver focuses on the child’s attentions and the quality of the interaction.

Episodic Symbols

Describe the ability to perceive, process, and use internal representations that include the self and the caregiver through emotional involvement in simple, everyday occurrences as the dimension of time begins to take on meaning. These are simple scenarios.

Example 1 Waiting eagerly for food while mom cooks.

Example 2 Visiting the doctor, getting to know the range of emotion related to the visit, physical experience and more. As a result, developing a fear of visiting the doctor.

Possible Therapeutic Tools:

-

- Imaginary-Spatial Play: Play that encourages movement in space. The objectives of play are:

- A. Increasing mobility and awareness of the body and the environment.

- B. With time developing an awareness of the environment and others moving in the child’s personal space and the relationship between them and the child.

- Power Poses

- Imaginary-Spatial Play: Play that encourages movement in space. The objectives of play are:

Complex symbols,multi-modalitiesand abstract thinking

Symbols describing the child’s emotional processing ability in complex situations that incorporate sensorimotor components effectively increasing over time. A child who feels insecure in the educational setting will be able to invent a character, like Superman, and draw strength from this complex symbol to help him overcome his fears. A child who is dealing with difficulties regarding his parent’s separation can play the scenarios out and overcome them with imaginary play.

Possible Therapeutic Tools:

Dynamic drawing:

The caregiver helps the child to process and symbolize simple and complex emotions such as joy, anxiety, anger, overwhelm, etc. through dialogue and accompanying drawing which changes throughout the interaction. The drawing allows the child to internalize the dynamic emotional shift promoted by the drawing and visually illustrate to him abstract things like the feelings and thoughts of others.